When I say the terms "

monument" and "

memorial" what associations come up in your mind? (Picture, as an example of a classic monument, the Washington Monument,

featured in the last post.) Do any of these concepts make your list?

-

Massive: a monument/memorial is usually large, visually powerful, dominating the space it inhabits.

-

National pride / Nationalism: almost all monuments/memorials represent moments or people important to the standard historical story of the nation. Washington DC was full of monuments to presidents and wars considered important. Recently, as our standard history has expanded to include histories of civil rights and minority groups as important, new monuments of national pride have been built, such as the American Indian Museum and the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial.

-

Memory: countries build monuments/memorials in order not to forget.

It is the importance of this last concept,

memory, which is the motivation for various Holocaust Memorials all over the world. But if monuments represent national pride, how can you build a Holocaust memorial when the Holocaust was a moment of national shame, mistakes and shortcomings in humanity? Countries like the US and Switzerland tightly restricted the number of Jewish refugees they accepted despite news of persecution; countries like France, Austria, and Italy were complicit with Nazi anti-semitic requests for most of the war. Of course the most extreme national shame is felt in Germany.

World-wide and in Germany, artists are struggling to build memorials that keep memory of the holocaust active, and inspire further learning and personal connections to the holocaust stories while resisting the traditional dominating, pride-filled structures.

Just one example, although there are an number of powerful ones:

The Aschrott Fountain Memorial by Horst Hoheisel, in the German city Kassel.

Hoheisel was commissioned to build a memorial on the place in the town square where in pre-Nazi times, a fountain had stood. This

fountain had been destroyed in the Nazi era because its donor, Sigmund Aschrott, was a Jew, even as

the donor, the donor’s family and over 3,000 other Jews were forcibly

removed from Kassel and sent to concentration camps. After the war, until Hoheisel's commission in 1987, the hole in the ground where the fountain had been was alternately left untouched, or planted with flowers.

Original Aschrott Fountain, 1908-1939, Kassel

In 1987, the city of Kassel, and Horst Hoheisel agreed that the story of this fountain, representing both the pre-Nazi Jewish contribution to the city, as well as, in its removal, horrific anti-semitism deserved a memorial. But Hoheisel did not want to build some massive monument on top of the empty space left by the fountain, where people might come once, and quickly forget about the story it represented. Instead, Hoheisel

highlighted the aspect of

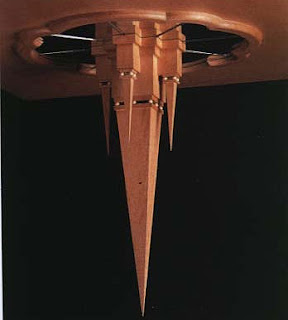

emptiness: the Jews had been removed, and Kassel was left with a hole in its culture, history and the hearts of the remaining citizens. He did not build upward, but dug out a mirror image of the

original Aschrott fountain under the ground at the site. The monument literally points visitors’ thoughts to the story beneath the

surface. Particularly interesting, visitors interact with the memorial not by looking at it as they stand in front of it, but by looking down as they stand on top of it. Thus what Hoheisel build acts more like a pedestal than like a complete monument. When visitors stand on it,

they, their thoughts, memories and experiences are the real monument.

Horst Hoheisel, Aschrott Fountain Memorial, 1987. Above: what the memorial looks like to visitors. Below, what the memorial looks like underground.

I think artists in countries like the US can learn from memorials like these. The US too has moments in history which should never be forgotten or downplayed, but which aren't exactly reasons for national pride (slavery and its legacies of racism, and the vast destruction of Native American people and cultures to name two.) How can these best be memorialized and remembered in art?